A new type of academic program is taking root in American universities, funded by conservative donors and state governments. These centers and institutes are dedicated to the study of Western civilization, classical texts, and the 'great books,' aiming to introduce a different perspective into what they see as a predominantly left-leaning humanities landscape.

From Florida to Utah, these initiatives are creating new curricula and faculty positions focused on classical philosophy and American founding principles, even as traditional humanities departments face budget cuts. This has sparked a debate on campus about the future of higher education and the meaning of intellectual diversity.

Key Takeaways

- New academic centers focused on Western civilization and classical studies are being established at major US universities.

- Funding often comes from external conservative donors or direct state legislative action.

- These programs aim to counter a perceived left-wing bias in academia and promote viewpoint diversity.

- The trend creates an unusual situation where classical humanities are expanding in some areas while being cut in others.

- Critics raise concerns about external influence on curricula and the potential for creating ideological echo chambers.

A New Direction in Higher Education

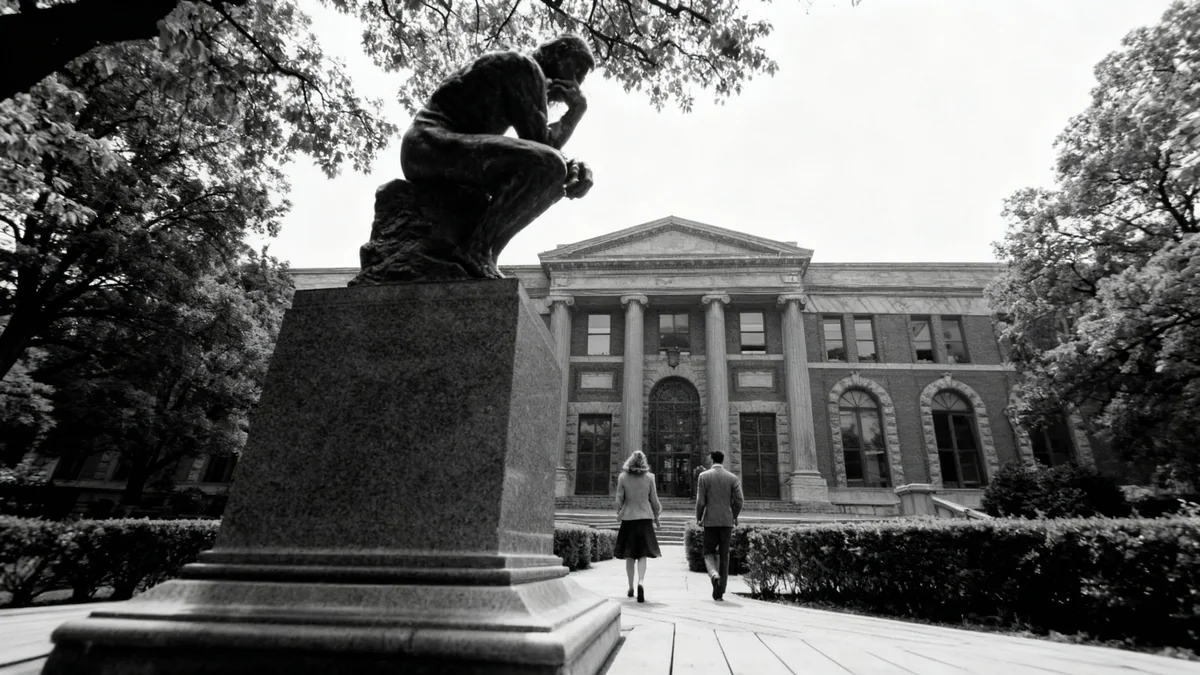

Across the United States, a significant shift is underway in the humanities. Universities are launching new programs with names that often include words like 'civic,' 'classical,' or 'freedom.'

Institutions such as the University of Florida, the University of Texas at Austin, and Stanford University are now home to these specialized centers. The University of Florida's Hamilton School for Classical and Civic Education, for instance, offers courses like “Great Books of the Ancient World” and “Liberty and Order.”

These programs represent a deliberate effort to reintroduce a curriculum centered on the Western canon, Christian thought, and the philosophical underpinnings of the American republic. This comes at a time when many traditional language and literature departments are struggling for funding and enrollment.

An End-Run Strategy

Some observers describe the creation of these freestanding centers as a strategic move by university administrators and state governments. According to Massimo Faggioli, a professor of theology who formerly taught in the U.S., this approach allows for the introduction of conservative-coded academic spaces while bypassing potential resistance from existing faculty departments.

Funding and Influence

The financial backing for these initiatives is a key part of the story. Much of the funding originates from outside the universities, either from private conservative donors or through specific allocations from state legislatures.

In a notable example, the Utah state government recently passed a law not only establishing a Center for Civic Excellence at Utah State University but also granting it authority over the university's general education requirements. Students there will now be required to study foundational texts from figures like Plato, Shakespeare, and Adam Smith.

Record-Breaking Grant

The National Endowment for the Humanities recently announced its largest grant ever, awarding $10.4 million to the Tikvah Fund, a conservative Jewish organization. A portion of these funds is designated for developing university courses in partnership with new Western civilization bachelor's degree programs.

This external influence has raised concerns among some faculty members, who view it as a potential threat to academic autonomy. At both Utah State and the University of Florida, reports indicate that the new centers were established without a formal request from the universities themselves, leading to criticism of a top-down imposition.

Debate Over Viewpoint Diversity

Proponents of these centers argue they are essential for correcting an ideological imbalance on college campuses. William Inboden, an executive at the University of Texas at Austin, has suggested that public trust in higher education has eroded partly due to a perception that universities have turned against traditional American values.

The stated goal is often to enhance viewpoint diversity by ensuring conservative and classical liberal perspectives are represented in teaching and research. Josiah Ober, a professor at Stanford, acknowledged that a concern for viewpoint diversity is a motivating factor for the legislators who have established some of these centers.

"One of the dangers of these centers is that you could end up with the same kind of groupthink that they were concerned about, just going in the other direction."

Musa al-Gharbi, Sociologist

However, critics point to a potential hypocrisy. Sociologist Musa al-Gharbi notes that while conservatives advocate for these new programs, some are simultaneously involved in efforts to defund or eliminate academic programs they find objectionable, such as women's and ethnic studies. This, he argues, can make the push for intellectual pluralism feel disingenuous and risks isolating the new centers from the broader university community.

The People and the Philosophy

The faculty hired by these new centers are often serious scholars whose work may not fit neatly into mainstream academic departments. Al-Gharbi observes that some of these academics might not have found positions elsewhere because their research is considered too conservative or interdisciplinary.

The fellows at UT Austin's Civitas Institute, for example, include conservative economists, law professors, and philosophers. Among them is John Yoo, a former White House official known for authoring legal memos on the use of torture during the George W. Bush administration.

Not Just for Conservatives

Despite the conservative backing, academics and observers note that the student body and even some faculty in these programs are not ideologically uniform. Zena Hitz, a tutor at St. John's College, which has long taught a 'great books' curriculum, points out the tradition's historical bipartisan appeal.

She explains that conservatives are drawn to the preservation of the Western canon, while progressives often appreciate the open-ended, discussion-based style of learning that empowers individual development. Hitz recounted teaching a course on the Bible where devout Christians and left-wing activist students found common ground in rigorous textual analysis.

This diversity is echoed by others. Dhananjay Jagannathan, a philosophy professor at Hunter College, mentioned knowing a self-identified socialist who was hired to teach in one of these programs. Similarly, Charles McNamara, a classics professor, observed that students drawn to the classics come from all walks of life.

An Uncertain Future

While these new centers are creating jobs in a difficult academic market, experts caution against viewing it as a wholesale revival for the humanities.

The number of new positions is small compared to the overall decline in humanities faculty jobs since the 2008 financial crisis. As Professor McNamara put it, quoting Aristotle, "One swallow does not make a summer."

The long-term impact of these centers remains to be seen. They could successfully foster a new generation of scholars dedicated to classical thought and broaden intellectual discourse on campus. Alternatively, they could become isolated ideological enclaves, further polarizing an already divided academic world. For now, they represent a new and contested frontier in the ongoing culture wars over American higher education.