A new report from Harvard's Office of Undergraduate Education has revealed that over 60% of all grades awarded to undergraduate students are A's, a dramatic increase that faculty members believe is undermining the university's academic mission. The findings have prompted a faculty committee to consider significant changes to the grading system, including the introduction of an A+ grade.

The 25-page report, released to faculty and students, highlights a trend that has accelerated over the past decade. It concludes that the current system is "failing to perform the key functions of grading" and is damaging the academic culture at one of the world's most prestigious universities.

Key Takeaways

- Over 60% of undergraduate grades at Harvard are now A's, compared to just 25% two decades ago.

- The median GPA for the graduating Class of 2025 was 3.83, and the median grade has been an 'A' since the 2016-2017 academic year.

- A faculty committee is considering proposals to introduce a limited number of A+ grades and to include the median course grade on student transcripts.

- Faculty report pressure to award higher grades due to course evaluations and student expectations, despite feeling that the grades do not always reflect the quality of work.

A System Under Strain

The report, authored by Amanda Claybaugh, Dean of Undergraduate Education, presents a stark picture of grade inflation at Harvard College. The data shows a steady climb in high marks, which spiked during the remote learning period of the Covid-19 pandemic and has since remained at an elevated level.

This phenomenon, often called grade compression, means that it is increasingly difficult to distinguish between good, very good, and truly exceptional student performance. The report states that "nearly all faculty expressed serious concern," perceiving a significant misalignment between the grades awarded and the actual quality of student work.

By the Numbers: Grading at Harvard

- Class of 2015 Median GPA: 3.64

- Class of 2025 Median GPA: 3.83

- Proportion of A's in 2005: Approximately 25%

- Proportion of A's Today: Over 60%

While previous analyses were cautious about labeling the trend as inflation, suggesting student work might be improving, this new report is unequivocal. It asserts that the system is not just compressed but inflated, failing in its primary purpose of evaluation.

"Our grading is too compressed and too inflated, as nearly all faculty recognize; it is also too inconsistent, as students have observed," Claybaugh wrote. "More importantly, our grading no longer performs its primary functions and is undermining our academic mission."

Faculty and Student Pressures

The report delves into the complex factors driving this trend. It suggests that faculty members face multiple pressures to be more lenient with grading. One significant factor is the university's course evaluation system. Instructors worry that assigning lower grades could lead to negative reviews, potentially harming their career prospects.

Another element is a decade-long institutional push for faculty to be more sensitive to students arriving at Harvard with varying levels of high school preparation. According to the report, many instructors, unsure of the best way to provide support, have resorted to simply being more lenient graders.

Students have also contributed to the pressure. The report notes an "increasingly litigious" attitude among some students who challenge their grades, adding another layer of complexity for instructors.

Is Student Effort Declining?

Despite the rising grades, the report cautions against assuming that students are working less. Self-reported data from course evaluations indicates that the average time students spend on coursework outside of class has remained stable, and even slightly increased, over the past 20 years.

In the spring of 2025, students reported working an average of 6.46 hours per week on coursework, compared to 5.85 hours in 2015. "Our data suggest that students are working as hard as they ever have — if not more," Claybaugh noted.

However, this data conflicts with the perceptions of some faculty, particularly in the humanities. Some professors reported needing to shorten reading assignments, switch from novels to short stories, and face increasing complaints about the workload. This suggests a potential disconnect between hours worked and the depth of academic engagement.

A Longstanding Concern

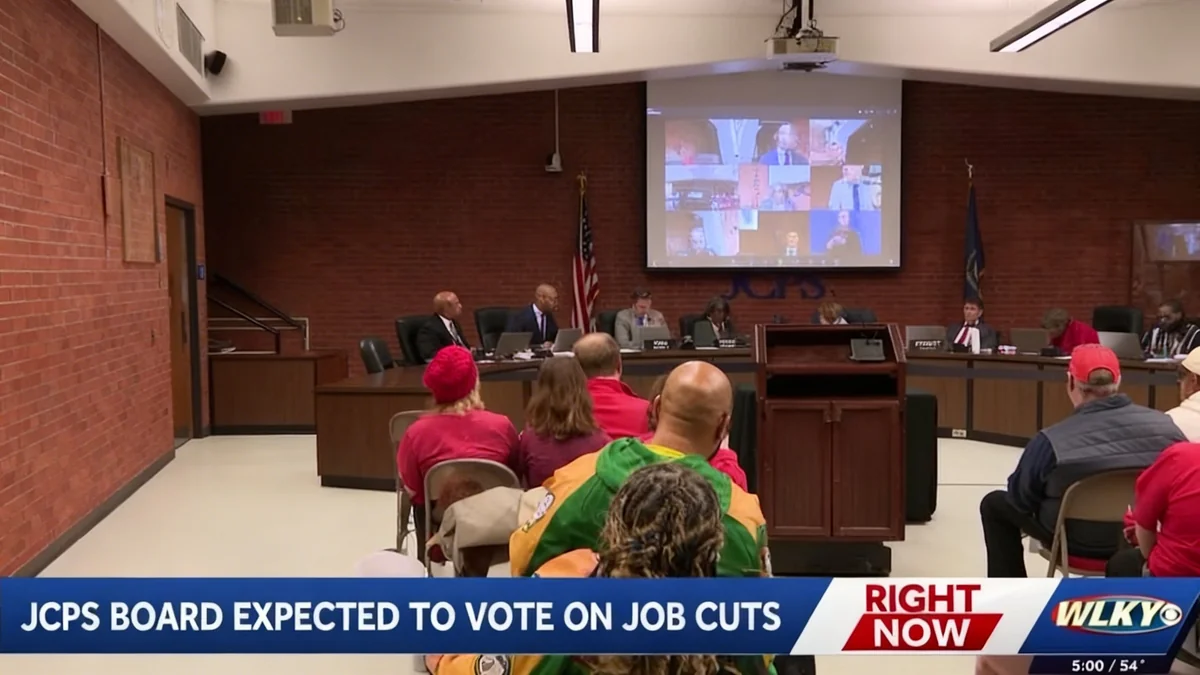

Concerns over grade inflation at Harvard are not new. Reports on the topic have surfaced periodically for years. As far back as two years ago, a faculty report highlighted the issue of skyrocketing undergraduate marks. The latest findings have brought the issue back into the national spotlight, prompting a more urgent call for reform within the university.

Searching for Solutions

In response to these findings, a faculty committee is actively exploring several potential reforms to restore meaning and rigor to Harvard's grading system. The proposals aim to provide more detailed feedback and create greater differentiation among student performance levels.

Among the leading proposals are:

- Introducing the A+ Grade: Currently, an 'A' is the highest possible grade. The committee is considering allowing faculty to award a limited number of A+ grades to recognize truly exceptional work. "Permitting faculty to award a limited number of A+s in each course would increase the information our grades provide by distinguishing the very best students," the report states.

- Adding Median Grades to Transcripts: Another significant proposal is to include the median grade for each course on a student's official transcript. This would provide context for an individual's grade, showing how they performed relative to their peers in that specific class.

- Encouraging In-Person Exams: The report suggests that a return to more traditional, seated exams could be beneficial. This is seen as a practical measure in the age of generative AI and a way to encourage students to engage with all course materials, which tends to result in a wider distribution of grades.

- Standardizing Grading: The report also advocates for greater consistency in grading between different sections of the same course, addressing a common student complaint about fairness.

Any major changes to the grading system, such as the introduction of an A+ or adding median grades to transcripts, would require a formal vote by the full faculty. The ongoing discussions signal a serious effort by the university to address what many see as a critical issue for its academic integrity.