An educational crisis is unfolding across Michigan as student absenteeism rates remain among the highest in the nation, impacting learning for all students and leaving educators struggling to keep pace. Despite a slight improvement from pandemic highs, nearly one in three students in the state is still missing a significant amount of school, a problem compounded by a lack of a unified state-level strategy.

Last year, 28% of Michigan's public school students were chronically absent, meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year—equivalent to 18 days or more. The situation is so severe that one in ten students missed seven weeks or more of class time. This trend is not only hampering the academic progress of absent students but also slowing down instruction for their peers who attend regularly.

Key Takeaways

- Michigan's chronic absenteeism rate was 28% last year, significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels and worse than neighboring states like Ohio and Indiana.

- The high number of absences forces teachers to delay new lessons, which negatively affects the academic performance of all students in a classroom.

- Unlike states that have passed comprehensive legislation, Michigan relies on local districts to manage attendance, a strategy that has proven ineffective.

- A cultural shift since the pandemic has led many parents to view school attendance as less critical, contributing to the problem.

The Ripple Effect in the Classroom

The impact of empty desks is felt daily by teachers across the state. In Mount Pleasant, first-grade teacher Danielle Bruursema frequently finds a quarter of her 24 students missing on any given day. She notes the immediate effect this has on young learners.

"It compounds on them very quickly," Bruursema said. "And it’s very very impactful to their ability to grow academically."

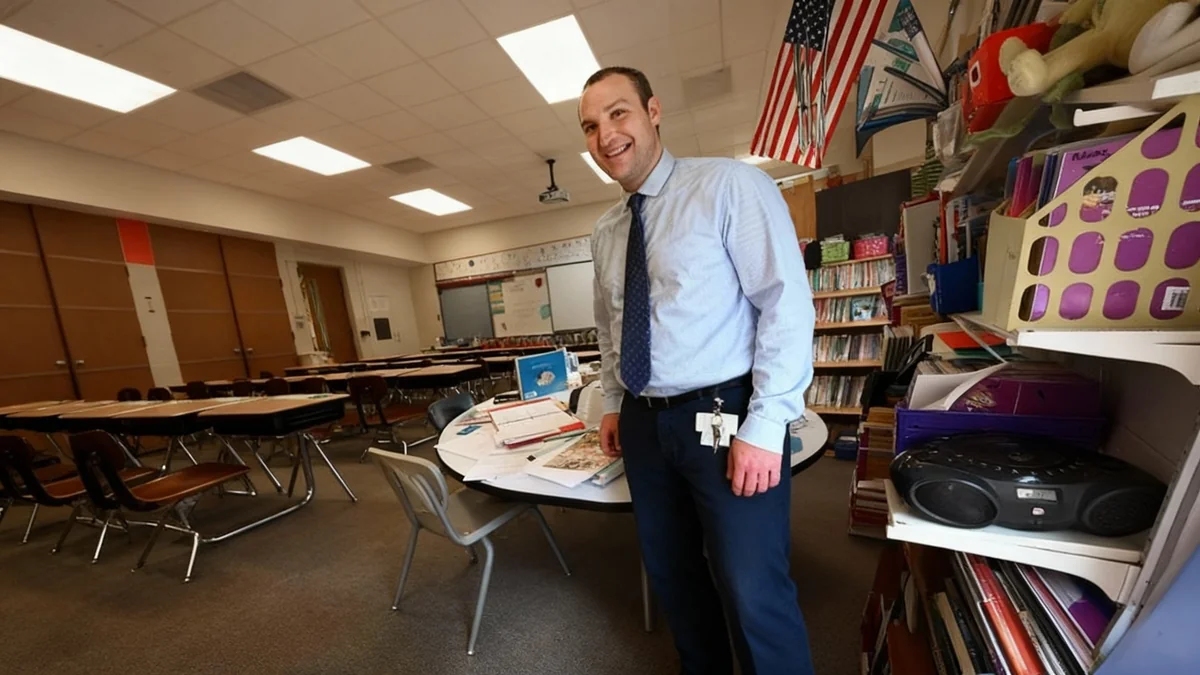

The challenge is not limited to elementary schools. Michael Adams, a third-grade teacher in Holt, directly links rising absenteeism to falling standardized test scores. He reported having only five days with full attendance in the first eight weeks of the school year. The constant need to catch up absent students put his class a week and a half behind schedule for the crucial M-STEP tests.

"You look out and there are 16 kids in the class, and you think, ‘I can’t teach anything new today,’” Adams explained, highlighting the difficult decisions teachers must make that ultimately slow down the entire class.

By the Numbers: Michigan's Absenteeism

- 28% of students were chronically absent last year.

- 1 in 10 students missed seven or more weeks of school.

- 30.7% of students in the Holt school district were chronically absent.

- $11.5 million in funding penalties will be issued to districts for low attendance days in the 2024-25 school year.

A Shift in Parental Attitudes

Educators and administrators point to a significant cultural change since the COVID-19 pandemic. The period of remote learning and relaxed sickness policies appears to have altered how many families perceive the importance of daily school attendance. What was once a point of pride—perfect attendance—is now often seen as optional.

"The culture was that school was mandatory, that missing was not OK," said Bob Kefgen, associate director of government relations for the Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals. He noted that after years of remote classes and health advisories to stay home when sick, the general attitude has fundamentally changed.

This sentiment is echoed by parents like Ann Arbor's Megan Kanous. She recalled hesitating to take her child out of kindergarten for a family trip years ago. "Now, I look back on that and I’m like, ‘gosh we could have taken those two days like that would have made some memories,’” she said, illustrating the relaxed view many now hold. Ann Arbor Public Schools has seen its chronic absenteeism rate nearly triple to 35.8% since the pandemic.

State Policy Lags Behind National Efforts

While absenteeism has become a national issue, Michigan's response has been noticeably slower than that of other states. The state currently follows a policy of local control, leaving individual districts to devise their own attendance strategies. This has led to an inconsistent and often ineffective approach to a statewide problem.

How Other States Are Responding

In contrast to Michigan's hands-off approach, several states have enacted robust legislation:

- Indiana passed laws requiring real-time absence reporting and mandatory parent interventions, which are already showing positive results.

- Connecticut requires schools with high absenteeism rates to form dedicated teams to improve attendance.

- Iowa mandates that districts create prevention plans and involve law enforcement if necessary.

Sixteen states and Washington D.C. have also joined a national project aiming to reduce chronic absenteeism by 50% within five years. Michigan is not part of this initiative.

Michigan’s compulsory attendance law is described as vague, allowing districts to set their own definitions for truancy and excused absences. Sarah Lenhoff, an education professor at Wayne State University, noted this lack of clarity makes enforcement difficult. Many districts are also hesitant to take legal action against parents, fearing it could worsen a student's home situation.

Legislative action has stalled. A 2017 bill to create statewide attendance standards failed, and a 2020 law removed minimum jail time for parents who don't comply with attendance laws. State Senator Dayna Polehanki, Chair of the Education Committee, has stated she wants to make absenteeism a priority but is uncertain what new legislation would involve.

Searching for a Systemic Solution

State education officials say they are addressing the issue. The Michigan Department of Education has implemented an Early Warning Intervention and Monitoring System (EWIMS) and is piloting a data-tracking program in about 60 districts. However, the state's official long-term goal is to reduce chronic absenteeism to 26.17%, a rate that would still leave it with one of the worst records in the Midwest.

Educators on the ground are pushing for a more urgent and coordinated response. Keith Seybert, a middle school principal in Midland, is actively trying to shift the culture back by emphasizing the importance of being in school even if a student isn't feeling 100%.

Jason Mellema, superintendent of Ingham Intermediate School District, voiced the frustration felt by many education leaders.

"I don’t think there’s enough light being shone on this problem. Pockets is not a systemic solution. We need to come up with a better way (where) we’re all committed to students being at school. If other states can do it, we can do it."

As the state continues to grapple with the academic fallout from the pandemic, the crisis of empty classrooms presents a fundamental barrier to recovery that experts say requires immediate and decisive action from state leaders.